The Sanshiro Sugata Legacy

This year marks the 80th anniversary of Akira Kurosawa’s Sanshiro Sugata: Part II, the 1945 sequel to his original feature, the debut which launched his career. His first Sanshiro Sugata story, an influential martial arts drama, was released in 1943 and forged a path for one of the twentieth century’s most important filmmakers. To coincide with this milestone, it felt timely to revisit and attempt to shine a light on the legacy and impact of this overlooked double-bill.

With a legendary filmmaking career spanning classics like Rashomon, Seven Samurai, Yojimbo, Sanjuro, Ran and so many others, it’s easy to overlook some of the deeper cuts in such a vast, varied career. However, for any fan of Asian cinema, it’s impossible to downplay the importance his early work holds, and the ripple effect of work such as this. The debut of Sanshiro Sugata followed more than five years of second and third unit directing, after which Kurosawa was finally permitted to helm a project of his own.

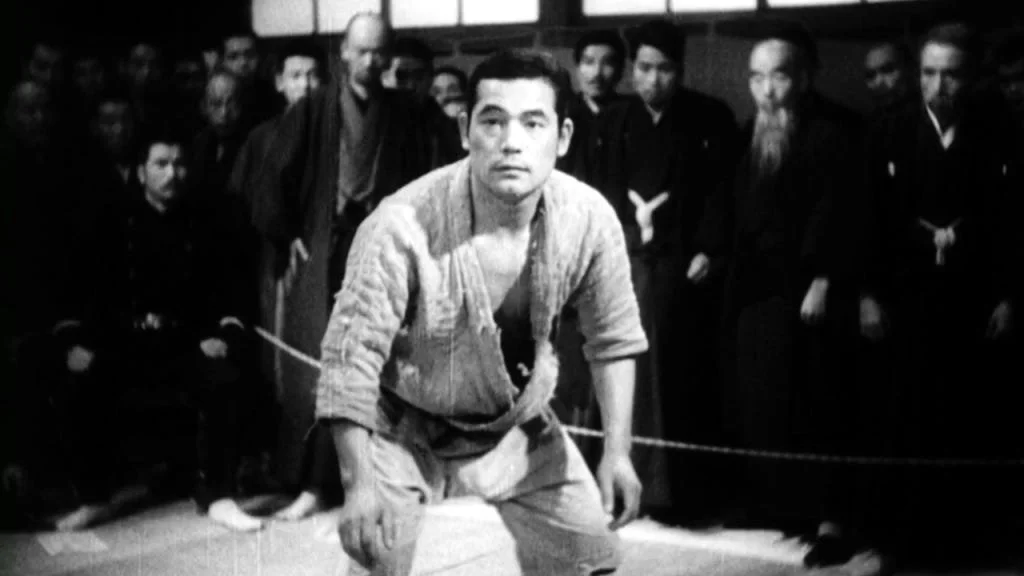

Adapted from the (then recent) 1942 novel by Tsuneo Tomita, inspired by famous judoka Shirō Saigō and the Kodokan–Totsuka rivalry of the 1880s, the prospect of dramatising this book and its Japan-centric themes were deemed safe enough territory, given government censorship during World War II. With the titular hero portrayed by wartime star, Susumu Fujita (later cast in The Hidden Fortress), this noble figure takes a spiritual journey through the study and practice of judo, while coming to terms with his social responsibility and place in the world. Despite judo being a central theme, the historic tale infuses many of the universally human themes and explorations from Kurosawa’s later work, with characters shown to be interesting and complex.

Following the first film’s success, the Japanese government undoubtedly saw potential for rousing propaganda on the big screen, and ordered the production of a follow-up. While Kurasawa seemed to speak well of the first production, he also described the censorship evaluation process as similar to "being on trial". Nonetheless, the sequel commenced production, shot in early 1945 towards the end of the war. This time, the story follows Sanshiro continuing his pursuit for judo mastery, while battling oppressors by way of honour on the mats, even going head-to-head with a tough American boxer.

Unlike the first film, far more subtle in its storytelling, the sequel is considered an outright propaganda film, and often dismissed as a result. It still features many of Kurosawa’s trademarks, and much of the cast returned to continue this judo master’s story. Despite criticism, the nationalism on display is not dissimilar to other films of the genre. With the main character setup as a nationalistic hero, in this case portraying Japan’s strength and the superiority of judo vs. Western boxing, these same tropes would inform plenty of Asian fight films in later years, from Bruce Lee’s Fist of Fury to Donnie Yen’s Ip Man franchise, and countless Hollywood blockbusters.

Remarkably, the original film saw no major international release until more than 30 years later in 1974, and would become a much-loved staple in Kurosawa’s early career. As a hungry filmmaker, more than ready for his debut after working on so many other sets, the Sanshiro Sugata films, impressively, feature many of his directorial trademarks, such as the wide cinematic framing of action scenes, his use of slow motion, weather patterns depicting drama onscreen, and the use of wipes as a transition in the edit.

Kurosawa deployed his storytelling techniques and visuals to create an early martial arts action saga, not to mention a symbolic portrayal of judo, jiu jitsu and, broadly, Japanese martial arts philosophy. The fight scenes, while far less violent by today’s standards, still feel real and grounded, unlike the stylised sword battles he would later create. Here, the actors are quite clearly rarely, if ever, doubled, and taking hits, throws and applying real application to the techniques. The sequel’s finale was also filmed outdoors in real snow, with Susumu Fujita braving the cold elements during his climactic fight.

There can be no doubt that these early gems from one of the world’s greatest filmmakers played a key role in setting a cinematic benchmark, whether Kurosawa knew it or not at the time. My feeling is that he didn’t necessarily realise the scope of influence it would take on. Yet, these films helped define a style, philosophy and physical approach for crafting dramatic, emotionally-driven action cinema, which is still going strong today. As both early examples of Kurosawa’s creative output, and important films in the history of martial arts, the Sanshiro Sugata films hold their place in the cinematic arena.